The US Congress has agreed on much larger budgets for science agencies than those proposed by US President Donald Trump. Credit: Douglas Rissing/Getty

The US Congress is poised to approve legislation rejecting the huge and unprecedented cuts to science sought by the administration of US President Donald Trump.

Under the latest deal, announced on 20 January, the US National Institutes of Health would see its budget increase by around 1% percent this year — in sharp contrast to the 37% cut proposed by the White House. Lawmakers have until 30 January to finalize the NIH deal and other spending legislation to avoid a partial government shutdown, which would be the second closure in less than three months.

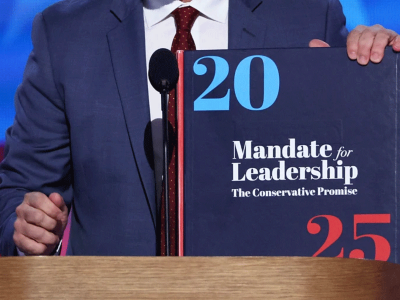

How Trump is following Project 2025’s radical roadmap to defund science

The NIH agreement follows separate legislation approved by Congress on 15 January that would minimize cuts to most of the other main science agencies. Overall, spending on research and development that is not related to national defence is projected to decline by 3—7%, far less than the 33% cut sought by Trump, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Washington DC. Total investments in basic research would actually increase by more than 2%.

“This is good news in comparison to last year”, when the Trump administration put forward its spending plan, says Alessandra Zimmermann, who tracks science budgets and policy at AAAS. Prior to that, however, “these numbers would have felt catastrophic,” Zimmermann says, and it’s still an open question whether the administration will actually spend the money as directed by Congress.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy did not immediately respond to questions about its spending plans.

Small raise for NIH

Under the proposed agreement, the NIH budget would rise by US$415 million to $48.7 billion for 2026. The agreement would also preserve the agency’s current structure of 27 institutes and centres. (The Trump administration had proposed in May to cut the agency’s budget to $27.9 billion, eliminate four of its institutes and centres and consolidate the remaining 23 into eight institutes.)

This slim increase is “good news”, says Jeremy Berg, a former director of an NIH institute who is now a data scientist at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. “It could have been much worse.” But he adds that the increase does not keep pace with inflation, so it would effectively be a slightly reduced budget in terms of purchasing power.

A sticking point in negotiations became the agency’s approach to so-called ‘multi-year funding’, in which a project’s budget is allocated all at once, rather than one year at a time. In 2025, the agency funded more than one-quarter of projects using this mechanism, compared with less than 10% in 2024, Berg estimates. As a result, the number of grants that received NIH funding was 24% lower than the average for the previous ten years.

How Trump 2.0 is slashing NIH-backed research — in charts

The proposed bill would prevent the NIH from expanding the proportion of new grants with multi-year funding beyond the 2025 level. That is a far cry from the Senate proposal to cap this form of funding at 2024 levels, which would have all but restored the typical model of funding one year at a time.

Although the Trump administration wanted to expand the programme to encompass half of new awards, the 2025 level would still put a lot of pressure on the research workforce, says Jenna Norton, a programme officer at one of NIH’s institutes who was placed on administrative leave in November. “This will make getting awards increasingly competitive and drive people out of science,” she says. “It’s a way to fund less science with the same amount of money.”

The NIH did not respond immediately to a request for comment on this issue.